In the frozen expanses of the Arctic, where temperatures plummet to extremes, the muskox stands as a testament to nature’s ingenuity. Cloaked in a dense undercoat of qiviut—the Inuit term for its inner wool—this resilient animal has inspired modern textile innovations. Unlike synthetic fibers designed to mimic warmth, qiviut is a natural marvel, offering unparalleled insulation without bulk. Its fibers are finer than cashmere, eight times warmer than sheep’s wool, and remarkably lightweight. For indigenous communities and explorers alike, garments woven from muskox wool have become a lifeline against the polar cold.

The muskox’s survival in such harsh conditions hinges on its unique adaptation: a double-layered coat. The outer guard hairs repel wind and moisture, while the inner qiviut traps body heat. When shed naturally in spring, these downy fibers are gathered sustainably from the tundra or combed from domesticated herds. This process, rooted in traditional knowledge, ensures minimal ecological disruption. Unlike industrial wool production, which often involves heavy chemical processing, qiviut requires no bleaching or dyes—its natural hues range from soft browns to muted grays, blending seamlessly with the Arctic landscape.

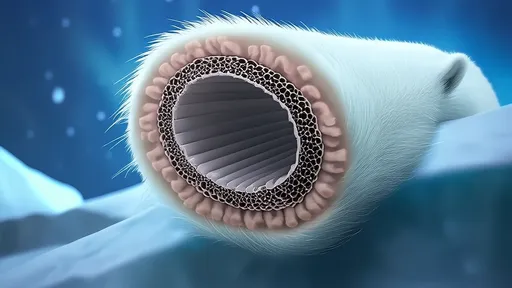

What sets qiviut apart is its molecular structure. Microscopic analysis reveals hollow cores within each fiber, creating tiny air pockets that enhance thermal retention. This biological design outperforms even advanced synthetic materials like Thinsulate. Moreover, qiviut lacks lanolin, making it hypoallergenic and odor-resistant—a boon for prolonged wear in remote expeditions. Arctic researchers have documented its ability to retain warmth even when wet, a critical advantage over down insulation, which clumps when damp. For mountaineers and polar scientists, qiviut-lined gloves or balaclavas often mean the difference between frostbite and survival.

The revival of qiviut weaving traditions among Inuit cooperatives has sparked a renaissance in ethical fashion. In Nunavut and Alaska, artisans spin the wool by hand using techniques passed down through generations. Each scarf or beanie tells a story of cultural resilience; patterns mimic ice formations or ancestral symbols. Luxury outdoor brands have taken note, collaborating with these communities to create high-performance apparel. A single qiviut sweater, requiring wool from three muskoxen and weeks of labor, can command prices upwards of $2,000—not just for its rarity, but for its irreplaceable properties.

Critics argue that scaling qiviut production presents challenges. Muskoxen number only about 150,000 globally, and their slow reproductive rates limit herd expansion. Yet proponents highlight successful conservation-combined initiatives in Canada and Greenland, where regulated hunting and fiber harvesting actually fund species protection. Meanwhile, textile engineers are experimenting with qiviut blends—combining 20% muskox wool with recycled synthetics to reduce costs while preserving 80% of its thermal efficiency. Such innovations could democratize access to this "Arctic gold."

Beyond functionality, qiviut embodies a philosophical shift in material science. In an era obsessed with high-tech synthetics, it reminds us that evolution spent millennia perfecting this fiber. As climate change alters polar ecosystems, the muskox’s adaptation strategies may hold clues for sustainable human innovation. Perhaps the future of extreme cold-weather gear lies not in laboratories, but in the windswept tundra—where a shaggy bovine continues to teach us about warmth, resilience, and coexistence.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025