As the summer sun begins to blaze, many pet owners find themselves contemplating a seasonal ritual for their long-haired companions—the summer shave. The image of a heavily coated dog or cat, panting in the heat, often triggers a well-intentioned impulse to provide relief by removing that thick fur. It seems like a logical solution, a direct way to combat the oppressive temperatures. However, the decision to shave a long-haired pet is far from straightforward and is a topic of considerable debate among veterinarians, groomers, and animal behaviorists. It is a decision that intertwines animal physiology, owner perception, and potential health consequences, making it a subject worthy of a deep and nuanced exploration beyond simple pros and cons lists.

The primary motivation for most owners is, without a doubt, the belief that they are helping their pet stay cool. We project our own human experiences onto our animals, reasoning that if we are uncomfortable in a heavy sweater, they must be miserable in a permanent fur coat. This anthropomorphic view, while coming from a place of love, fundamentally misunderstands how a dog or cat's body regulates temperature. Unlike humans, who sweat over most of their body to cool down, pets have a very different cooling system. Dogs primarily cool themselves through panting and by sweating minimally through their paw pads. Cats also use similar methods, including grooming, which allows saliva to evaporate from their fur for a cooling effect. Their coats are not merely decorative; they are a highly evolved thermoregulatory system.

A double-coated breed's fur, for instance, is a marvel of natural engineering. This type of coat consists of a dense, soft undercoat close to the skin and a longer, coarser layer of guard hairs on top. This structure is designed to act as insulation year-round. In the winter, it traps body heat to keep the animal warm. Crucially, in the summer, it works in reverse. The coat traps a layer of cooler air next to the skin, shielding the pet from the direct heat of the sun and preventing overheating. It functions much like the insulation in a thermos, keeping hot things hot and cold things cold. Shaving this coat away removes this built-in protective barrier, potentially exposing the skin to sunburn and actually making it harder for the animal to regulate its body temperature effectively.

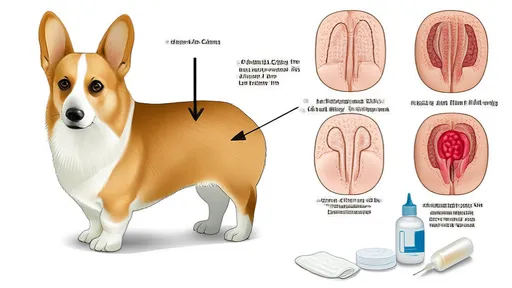

Furthermore, a pet's coat offers vital protection against environmental hazards. It is a first line of defense against sharp objects, abrasive surfaces, and biting insects. Without it, the skin becomes vulnerable to cuts, scrapes, and mosquito bites. Perhaps most dangerously, the risk of skin cancer from direct UV exposure increases significantly, especially for pets with light or pink skin. The fur also helps to prevent conditions like hot spots, which are moist, inflamed skin infections that can be exacerbated by moisture trapped against shaved skin. The coat wicks moisture away and allows for air circulation, which is ironically more effective at preventing overheating and skin problems than a close shave.

Beyond the physical risks, the act of shaving can have unintended psychological and behavioral consequences. For many animals, their coat is integral to their identity and sensory experience of the world. A drastic change in their appearance can be confusing and stressful. Some pets may become anxious, withdrawn, or even exhibit signs of embarrassment. There is also the very real risk of damaging the coat itself. In many double-coated breeds, shaving can permanently alter the texture and pattern of hair regrowth. The undercoat may grow back faster than the guard hairs, leading to a patchy, woolly, and unattractive coat that never fully returns to its original state. This condition, known as post-clipping alopecia, can sometimes be permanent, leaving the owner with a regrettable long-term problem that started with a short-term solution.

This is not to say that grooming is unnecessary in the summer; on the contrary, it is absolutely essential. The key, however, is the type of grooming. The most beneficial summer haircut is not a shave but a professional trim and thorough deshedding. A skilled groomer can thin out the dense undercoat—which is what causes most of the heat retention—while leaving the protective guard hairs intact. This process, often achieved with specialized tools like undercoat rakes and deshedding blades, allows the insulation system to function properly while significantly reducing the bulk and weight of the coat. Regular and frequent brushing at home is equally important. It removes dead hair, prevents painful matting, and stimulates the skin, all of which promote better air circulation and more effective temperature regulation.

Other cooling strategies are far more effective and safer than reaching for the clippers. Ensuring constant access to fresh, cool water and a shaded, well-ventilated resting area is paramount. Cooling mats can provide a comfortable spot for a pet to lie on, and scheduled walks during the cooler parts of the day, such as early morning or late evening, can prevent overheating during exercise. Even simple acts like offering ice cubes to lick or setting up a shallow kiddie pool for a dog to wade in can provide immense relief without any of the risks associated with shaving.

It is also critical to recognize that not all pets are the same. While shaving is generally discouraged for most double-coated breeds like Huskies, Golden Retrievers, and Maine Coon cats, there may be exceptions. For some single-coated breeds or pets with medical conditions requiring it, a shave might be necessary or beneficial. However, this should never be a decision made on a whim. It requires a consultation with a veterinarian or a professional groomer who understands coat types and breed-specific needs. They can provide tailored advice based on the individual animal's health, lifestyle, and the local climate.

In conclusion, the decision to shave a long-haired pet in the summer is a complex one, rooted more in human perception than in animal biology. The instinct to provide comfort is admirable, but it must be guided by knowledge rather than assumption. A pet's fur is a sophisticated biological system designed for their protection and comfort. Disrupting that system can lead to a host of problems, from sunburn and overheating to skin disease and permanent coat damage. The path to a happy and cool pet in the summer lies not in drastic measures but in consistent, proper grooming, intelligent management of their environment, and a commitment to understanding their unique physiological needs. The best way to show our love for our furry family members is often to trust in the natural defenses they already possess and to support them with informed and careful care.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025